By Holly A. Shapiro, Ph.D., CCC-SLP

I’ve often encountered the argument that “there is no evidence that teaching etymology helps students.” Well, I go back to Dylan William’s insights that we need to continue to challenge ourselves to think about “what might be,” about “what could be.” Here’s an example. Spelling has always come very easy to me. Despite that, a few words have remained elusive. A couple of weeks ago, determined to practice what I preach, I investigated permanent hoping to help myself out with that first “a”. Perminent? Permanent? I was never quite sure. A quick look at an etymology dictionary was all it took. Remain. It’s related historically. It shares meaning. There is a similarity in the spelling.

I shared my excitement on Twitter only to be told that there’s a better way and that would be to teach the student to pronounce it incorrectly as perMANent

/pəɹˈmænənt/

Frankly, I think this is messed up.

How is the kid supposed to remember which wrong way to say it? Is it permaNENT? PerMANent? What if they can’t remember which wrong way to say it?

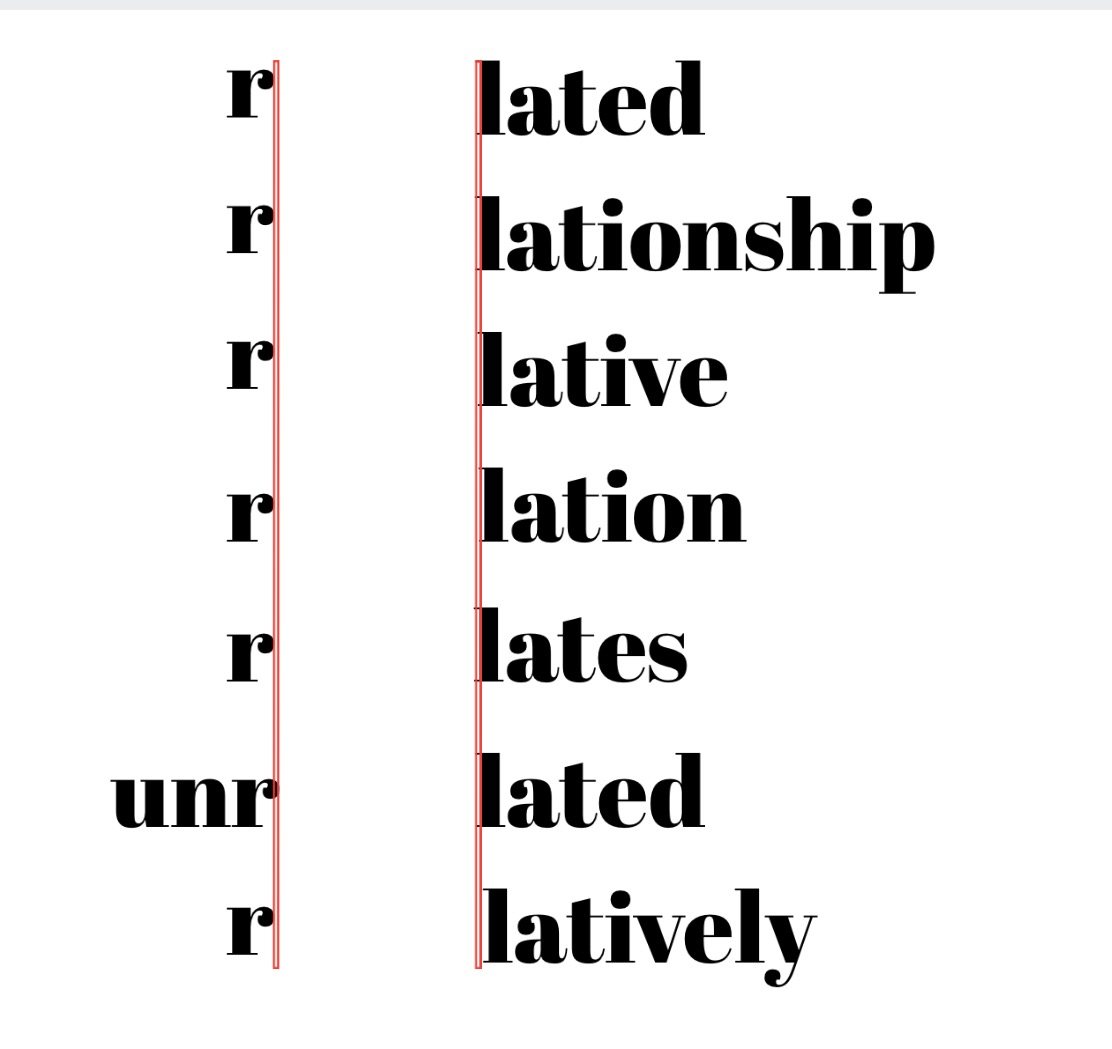

Permanent, however you pronounce it, has no connection to man. Where permanent and remain will always have something to do with the idea of “stay”. Always. Word parts that share meaningful and historical connections have a tendency to share similarities in spelling despite differences in pronunciation. That is the expectation in English. It’s how our writing system works.